Oral Health promotion

The threat of noncommunicable diseases and the need to provide urgent and effective public health responses led to the formulation of a global strategy for prevention and control of these diseases, endorsed in 2000 by the Fifty-third World Health Assembly (resolution WHA 53.17).

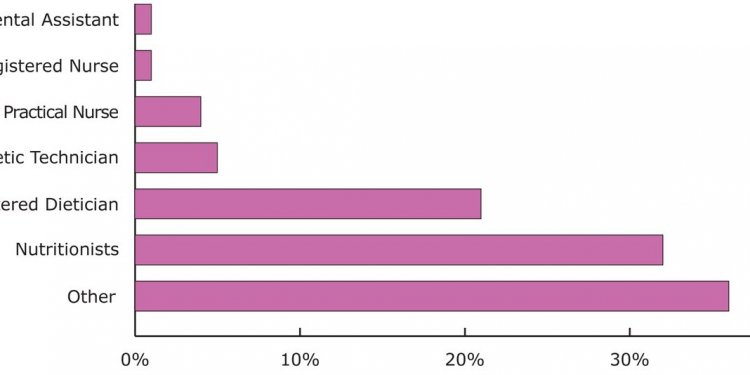

Priority is given to diseases linked by common, preventable and lifestyle related risk factors (e.g. unhealthy diet, tobacco use), including oral health. Key socio-environmental factors involved in promotion of oral health are outlined in Figure 5 which also shows some important modifiable risk behaviours.

FIGURE 5:

High relative risk of oral disease relates to socio-cultural determinants such as poor living conditions; low education; lack of traditions, beliefs and culture in support of oral health. Communities and countries with inappropriate exposure to fluorides imply higher risk of dental caries and settings with poor access to safe water or sanitary facilities are environmental risk factors to oral health as well as general health. Moreover, control of oral disease depends on availability and accessibility of oral health systems but reduction of risks to disease is only possible if services are oriented towards primary health care and prevention. In addition to the distal socio-environmental factors, the model emphasizes the role of intermediate, modifiable risk behaviours, i.e. oral hygiene practices, sugar consumption (amount, frequency of intake, types) as well as tobacco use and excessive alcohol consumption. Such behaviours may not only affect oral health status negatively as expressed by clinical measures but also impact on quality of life.

Clinical and public health research has shown that a number of individual, professional and community preventive measures are effective in preventing most oral diseases. However, optimal intervention in relation to oral disease is not universally available or affordable because of escalating costs and limited resources. This, together with insufficient emphasis on primary prevention of oral diseases, poses a considerable challenge for many countries, particularly the developing countries and countries with economies and health systems in transition.

Most of the evidence relates to dental caries prevention and control of periodontal diseases. Gingivitis can be prevented by good personal oral hygiene practices, including brushing and flossing which are important also to the control of advanced periodontal lesions. Community water fluoridation is effective in preventing dental caries in both children and adults. Water fluoridation benefits all residents served by community water supplies regardless of their social or economic status. Salt and milk fluoridation schemes are shown to have similar effects when used in community preventive programmes. Professional and individual measures, including the use of fluoride mouthrinses, gels, toothpastes and the application of dental sealants are additional means of preventing dental caries. In a number of developing countries the introduction of affordable fluoridated toothpaste has been shown to be a valuable strategy, ensuring that people are exposed appropriately to fluorides.

Individuals can take actions for themselves and for persons under their care, to prevent disease and maintain health. With appropriate diet and nutrition, primary prevention of many oral, dental and craniofacial diseases can be achieved. Lifestyle behaviour that affects general health such as tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption and poor dietary choices affect oral and craniofacial health as well. These individual behaviours are associated with increased risk of craniofacial birth defects, oral and pharyngeal cancers, periodontal disease, dental caries, oral candidiasis and other oral conditions.

Opportunities exist to expand oral disease prevention and health promotion knowledge and practices among the public through community programmes and in health care settings. Oral health care providers can also play a role in promoting healthy lifestyles by incorporating tobacco cessation programmes and nutritional counselling into their practices.

However, there are profound oral health disparities across regions, countries and within countries. These may relate to socioeconomic status, race or ethnicity, age, gender or general health status. Although common dental diseases are preventable, not all community members are informed of or are able to benefit from appropriate oral health-promoting measures. Under-served population groups are found in both developed and developing countries. In many countries, moreover, oral health care is not fully integrated into national or community health programmes.

The major challenges of the future will be to translate knowledge and experiences about disease prevention into action programmes. Social, economic and cultural factors and changing population demographics impact the delivery of oral health services in countries and communities and how people care for themselves. Reducing disparities requires far-reaching wide-ranging approaches that target populations at highest risk of specific oral diseases and involves improving access to existing care. Meanwhile, in several developing countries the most important challenge is to offer essential oral health care within the context of primary health programmes. Such programmes should meet the basic health needs of the population, strengthen active outreach to the community, organize primary care, and ensure effective patient referral.